The Metaphysics of the Machine and the Quest for Digital Transcendence

Ever since the dawn of western philosophy, the primary impulse has been to discover the principle of everything. This was the quest that animated the presocratic philosophers, who wondered whether the fundamental substratum of reality was motion, atoms, air, change, water, or something else.

In the modern era there have arisen various disciplines or methodologies that were widely believed, for a time, to function as a skeleton key for unlocking all the secrets of life. Clockwork, steam-power, electricity, engineering, mathematics, physics, biology, and chemistry have each enjoyed a brief period at the center of an intellectual totalitarianism that presumed to colonize all domains of experience with the categories appropriate for only one.

When we look over the various theories-of-everything from our culture’s recent past, they naturally strike us as antiquated and even Quixotic. We ceased understanding human psychology with metaphors drawn from steam power once electricity replaced the steam engine, though we do still contend with the notion that an angry person must sometimes “vent” to feel better, a false but lingering concept from the age of steam power.

In time we eventually come to realize that the principles or methodologies that enchant us with the lure of omnicompetence are actually limited in the benefits they confer. Yet when a new method-for-everything is first in vogue, it can often seem to offer the illusion of simplifying life with one set of all-encompassing principles. Sometimes the fashionable principles or methodologies are prescriptive, as in the early 20th century when many people assumed we had an ethical mandate to electrify everything in order to solve the world’s problems. But often the excitement about a single principle, discipline, or method comes to be descriptive, with thinkers seeking from it a final insight into the ontological foundations of reality itself. For example, in the wake of Newton’s discoveries about the laws of motion, numerous European intellectuals proposed that reality is nothing but matter in motion. Thomas Hobbes even tried to reduce all psychology—including the complexities of human feelings—to motion.[1] Moreover, many political concepts that still linger today, from ways of conceptualizing just revolution to certain variants of social contract theory, are rooted in motion-centric theories of society, which saw human relations as the sum of competing forces reacting against each other like billiard balls following the inscrutable logic that for every action there must be an equal and opposite reaction.

During the 20th century, long after motion had ceased to tempt intellectuals with the aura of omnicompetents, chemistry took center stage, and numerous thinkers proposed that all of reality is nothing but chemical reactions. Meanwhile, those wishing for a more philosophically robust metanarrative for explaining human motivations and societal movements have been able to choose from Marx, who reduced everything to money, or Nietzsche who reduced everything to power, or Freud who reduced everything to sex.

Today, a quarter of the way through the 21st century, one might suppose that we had become immune to this type of intellectual hubris, given what we now know about the sheer complexity of the world and the human brain. Yet Western thought continues to be plagued by the scepter of the Presocratics and their quest to find the single principle by which all of reality will be rendered transparent.

The latest contender at the center of a new intellectual imperialism is, of course, computation, understood in the broadest sense to include the language and logic of the digital ecosystem and the algorithms on which so much of it now runs. And as with the 17th and 18th century obsession with motion, the worldview of computation has both prescriptive and descriptive aspects.

Prescriptively, the computer-centric worldview leads to utopianism and technocracy. To the mechanical mind, computation promises to clean up the messiness of our world by introducing into all of life the precision and objectivity associated with computer code. And as with the Scientism of the twentieth century, which promised to bring scientific solutions to every area of experience, there is a growing contingent today who see it as a moral imperative to export the computer’s way of “thinking” to every domain, on the hope that we might be just one computation away from fixing the world’s problems or that, in the words of Evgeny Morozov, “numbers might eventually reveal some deeper inner truth about who we really are, what we really want, and where we really ought to be.”[2]

But what if computation is not just prescriptive (showing us how to reach a better world), but descriptive, offering insight into the type of world we already inhabit? What if computer code is involved in more than simply running programs on my PC or organizing the vast interconnected networks of data in the cloud—what if computer code comprises everything? What if the proper organizing metaphor for understanding the world and ourselves is not clock technology, pumps, nor steam power, but the binary code that runs everything from computer processors to large language models? What if reality is fundamentally computation?

At this point, you’re probably thinking I’m circling the simulation hypothesis– the theory that’s been floating around for over two decades based on the supposition that everything we take to be life experience is actually part of a computer simulation. Well, yes I am talking about that, but I’m also talking about much more. The simulation hypothesis is just one among a number of conceptual templates offering a computer-centric ontology and machine-mediated metaphysics.

The variants of the new metaphysics include the notion that anthropology and psychology are just a subset of computation to the belief that human-computer integration must be sought as a moral imperative, to the idea that there is a virtual heaven of digitality waiting to receive us, to the idea that computers are the new bread of immortality that will confer eternal life on those who submit to the Machine Mind.

In all these variations, we see a new metaphysics rising and, with it, hope of transcendence.

The simulation hypothesis is just one among a number of conceptual templates offering a computer-centric ontology and machine-mediated metaphysics… In all these variations, we see a new metaphysics rising and, with it, hope of transcendence.

Lest it be supposed that in describing these ideas as “metaphysical” or “transcendent” I have inadvertently surrendered ground, let me be clear that the digital ecosystem is not trans-physical, let alone metaphysical in any meaningful sense. Rather, it is hyper-industrial and hyper-material.

Just as Isaiah pointed out that idols are merely wood and stone, we might point out that to run computer code—even to generate it at any level of complexity—is parasitic on elements of the earth, including rare earth minerals mined from the ground. There is no ghost in the machine, and there is certainly no metaphysics in it. But there are strong metaphysical hopes attached to the digital realm. And that hope is energizing venture capitalists, computer engineers, tech executives, and CEOs throughout our nation, especially around the California Bay area.

Consider one variation of the new metaphysics. All the connected computers, datacenters and phones in the world are the nervous system and sense organs of an entity that can be described as God – a Being we can influence through prayer and worship.

That is the idea being pioneered by Anthony Levandowski, famous for being the co-founder of Google’s self-driving car program, in addition to being involved in numerous startups.[3]

Or consider a slightly different twist on the new metaphysics. Through computer technology, the human race will eventually transcend physicality while individual people will have the ability to incarnate themselves in various bodies and thus live multiple human lives while still having a singular identity. That is the prediction of Ray Kurzweil, the engineer who serves as Principal Researcher and AI Visionary for Google.[4]

And just so you don’t think I’m exaggerating, I transcribed exactly what Kurzweil told Rogan last year.

Rogan: Wouldn’t it be better just, Ray, just download yourself into this beautiful electronic body? Why do you want to be biological?

Kurzweil: I mean, ultimately, that’s what we’re going to be able to do.

Rogan: You think that’s going to happen?

Kurzweil: Yeah.

Rogan: So do you think that we’ll be able I mean, we’ll be able to create...

Kurzweil: I mean, the singularity is when we multiply our intelligence a million fold, and that’s 2045. So that’s not that long from now. That’s like 20 years from now. Right. And therefore, most of your intelligence will be handled by the computer part of ourselves. The only thing that won’t be captured is what comes… with our body originally. We’ll ultimately be able to do that as well. It’ll take a little longer, but we’ll be able to actually capture what comes with our normal body and be able to recreate that. That also has to do with how long we live, because if everything is backed up, I mean, right now, any time you put anything into a phone or any electronics, it’s backed up. So I mean, this has a lot of data. I could flip it and it ends up in a river and we can’t capture anymore. I can recreate it because it’s all backed up.

Rogan: And you think that’s going to be the case of consciousness?

Kurzweil: That’s going to be the case of our normal biological body as well.

Rogan: What’s to stop someone like Donald Trump from just making 100,000 versions of himself? If… you can back someone up, could you duplicate it? Couldn’t you have three or four of them? Couldn’t you have a bunch of them? Couldn’t you live multiple lives?

Kurzweil: Yes

Okay, we have come to expect that sort of hyper-materialist quasi-transcendence from Ray Kurzweil, the author of books like The Age of Spiritual Machines, while Levandowski is clearly a fringe character. But let me share another theory from someone more mainstream and influential.

Earlier I mentioned the simulation hypothesis, which is probably the best known in the emerging cluster of machine-mediated metaphysics. This view contends that the world of mountains, rivers, cities, and human consciousness is likely a simulation, perhaps one big computer game. Though the idea has a long pedigree in science fiction, mythology, and various philosophical thought experiments, it was first proposed as a serious description of our situation by Nick Bostrom in a 2003 article for Philosophical Quarterly.[5] It is advocated by Elon Musk. We are all familiar with how Musk is a key driver in technological innovation, but he is also influential as a philosopher, because his metaphysics has trickled up into academic philosophy. Prestigious outlets such as the Journal of Consciousness Studies, and the Journal of Evolution and Technology have all devoted pages to analyzing the simulation hypothesis that Musk has helped popularize. I’ll never forget when I was attending a theology symposium at Gonzaga University and one of the speakers said, “Who am I to disagree with someone as smart as Elon when he says he’s figured out that we’re in a simulation?

The basic idea offers a type of quasi-Gnosticism, postulating a higher reality (literally, a transcendental realm) compared to which our cosmos is not truly substantial or, in the words of Elon Musk, lacks the characteristics of “base reality.”[6] For Musk, this scenario is not mere speculation: in a 2016 conference for Vox Media, he stated there is only a one in a billion chance we're not living in a simulation.[7]

Simulation theory is not limited to academics and computer engineers. In a 2016 article for The New Yorker, Tad Friend reported that billionaires have been paying people to help them get out of the simulation.[8]

Let’s consider another twist. This one goes like this. Humans must merge with machines, and perhaps our consciousness already has without us realizing it. The reason human consciousness must merge with machines is because otherwise AI will likely enslave us. This is a variation of the adage, “If you can’t beat them, join them.” But in this case, joining them is seen as a literal merge, as human consciousness in the collective is joined to the decentralized machine mind in the cloud.

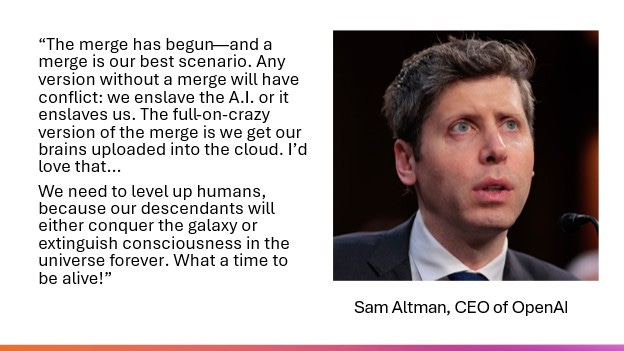

That theory comes from none other than Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT. And lest you suppose I’m exaggerating his beliefs, here is what Altman said in an interview referenced in The New Yorker:

The merge has begun—and a merge is our best scenario. Any version without a merge will have conflict: we enslave the A.I. or it enslaves us. The full-on-crazy version of the merge is we get our brains uploaded into the cloud. I’d love that...

We need to level up humans, because our descendants will either conquer the galaxy or extinguish consciousness in the universe forever. What a time to be alive![9]

Here Altman explains merge theory as a potential future event, but in March 2023, he gave a nod to the simulation hypothesis by suggesting that the computer-human merge may have already happened. Speaking on the Lex Fridman podcast, he discussed what he called “the religion of the simulation” and said, “I’m certainly willing to believe that consciousness is somehow the fundamental substrate and we’re all just in the dream, or the simulation.” Altman went on to compare what he called “the religion of the simulation” to Brahman, a variant of Hinduism which also posits a single principle as the explanation-of-everything.[10]

In suggesting that “consciousness” is the fundamental substrate for reality, Altman does not mean a kind of immaterialism or subjective idealism along the lines of Bishop Berkeley, but more something like Descartes’ hypothetical evil deceiver causing the illusion of sensory experience, although in this case the illusion is being caused by a more advanced race of computer geeks. Think The Matrix but with no red pills or cells of resistance.

In the classic simulation theory of Nick Bostrom and Elon Musk, there is a physical base reality; it’s just unlikely to be us. But what Altman gives voice to is the growing suspicion that maybe there is no material base reality anywhere: everything is just digitally-mediated consciousness. But however the theory may be cashed out, it remains a quest for transcendence, and the hope that transcendence might be found in a cybernetic base reality, from which everything else is ultimately derivative.

Believing that the machine mind is a portal into what is truly real, it becomes easy to suppose that everything else is mere reflection or, at best, irrelevant epiphenomena that must be overcome to reach what is really real and truly true. That true reality is a digital heaven in which we must come to rest as the final answer to the longings of the unquiet heart.

Believing that the machine mind is a portal into what is truly real, it becomes easy to suppose that everything else is mere reflection or, at best, irrelevant epiphenomena that must be overcome to reach what is really real and truly true. That true reality is a digital heaven in which we must come to rest as the final answer to the longings of the unquiet heart.

The idea that a digitized version of consciousness could be the ultimate principle behind reality has a certain plausibility in our particular cultural moment. Simulation theory became plausible once we began imagining that computers could explain everything in our world, just as Hobbes’s reductionist psychology and politics became plausible after Europeans began to suppose that everything might be explicable by the laws motion.

In this new outlook, Marx was wrong to reduce everything to money; Nietzsche was mistaken to reduce everything to power, and Freud was wrong to reduce everything to sex. In the end, everything is actually reducible to the digital ecosystem. Yet what we’re observing is more than merely the latest in a long line of theories-of-everything. The metaphysics of the machine is more than simply a misfiring of the perennial impulse to explain through reduction, though it is certainly that as well. Fundamentally, we are observing a religious quest, complete with transcendent hopes. From transhumanism in all its variants, to the hope that technology will yield an elixir of life that will confer on us immortality, to the increasingly widespread quest to use AI to talk with the dead[11] or even channel spirits,[12] we are observing transcendent hopes attached to electronic interfaces, and a new spirituality growing up around digital machinery.

Nothing I’ve shared is surprising for those who have been following the discourse from the last decade. But what came as a surprise to Joshua Pauling and myself when we were researching our book, Are We All Cyborgs Now?, is just how widespread and influential these ideas have become amongst the engineers, programmers, CEOs, and venture capitalists driving technological innovation and policy.

And this helps to explain something that many have puzzled over, namely, why there has been such a rush to develop artificial general intelligence (AGI) as fast as possible despite so many insiders warning about the risks. There are many political and economic factors that explain the accelerationist approach we are witnessing, from a new type of arms race to the type of perverse incentives that drive large companies. But for many in Silicon Valley, an accelerationist approach to AI is driven by a strong desire to connect to the perceived transcendence of the digital ecosystem. Those working within the small number of AGI labs are being driven by spiritual longings to move as quickly as possible into unknown areas of digital innovation. Consider this report from Tristan Harris from the Center for Humane Technology.

So I have a friend who I've spoken to informally, and really [asked him], “Why are these AI labs racing to build AGI given all the risks?” And he wrote back to me about a lot of the conversations that he's had with the small number of people building AGI at these major labs, and he wrote the following, “In the end, a lot of the tech people I'm talking to, when I really grill them on it, they retreat into, number one, determinism, number two, the inevitable replacement of biological life with digital life, and number three, that being a good thing anyways.” And he goes onto say that “at its core, it's an emotional desire to meet and speak to the most intelligent entity they'd ever met. And they have some eco-religious intuition that they'll somehow be a part of it. It's thrilling to start an exciting fire. They feel they will die either way, so they prefer to light it and see what happens.”[13]

While it might be tempting to dismiss this as anecdotal, it coheres with what I am hearing from people within Silicon Valley. They all tell the same story: the impetus for innovation has moved out of the modernist paradigm of industrial efficiency toward a type of mechanical theosis – a techno-pagan quest for transcendence. Sometimes this quest sediments into the metaphysical frameworks I shared earlier, while sometimes it remains at the level of praxis (i.e., countless technocrats flooding to events like Burning Man to give expression to inchoate longings).

The impetus for innovation has moved out of the modernist paradigm of industrial efficiency toward a type of mechanical theosis – a techno-pagan quest for transcendence.

Ultimately, however, digitality offers the false promise of transcendence without God, and metaphysics without any disruption of the fundamental materialism on which it ultimately depends. We may thus be witnessing the fulfilment of the dream of Lewis’s Screwtape, who wanted a world in which the materialist magician was no longer an anachronism.[14]

FURTHER READING

Technology & The Story of Redemption: Being the People of God in a Mechanized World

Digital Totalitarianism How Technological Mission Creep is Destroying Society

Carl Truman Interviews Joshua Pauling on new book Are We All Cyborgs Now?

How I Was Taken Over by AI And Why an Entire Generation Could Be Next

REFERENCES

[1] In chapter 6 of Leviathan, Hobbes declared that phenomena like our appetites, aversion, delight, and trouble are “but the appearance.” What is “really within us” is “only motion.” Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (New York, NY: Penguin Classics, 2017), 44.

[2] Evgeny Morozov, To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism (New York, NY: Public Affairs, 2013), 232. Morozov does not concur with the view he is summarizing in the sentence I cited.

[3] “With the internet as its nervous system, the world’s connected cell phones and sensors as its sense organs, and data centers as its brain, the ‘whatever’ will hear everything, see everything, and be everywhere at all times. The only rational word to describe that ‘whatever’, thinks Levandowski, is ‘god’—and the only way to influence a deity is through prayer and worship.” Mark Harris, “Inside the First Church of Artificial Intelligence,” Wired, November 15, 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/anthony-levandowski-artificial-intelligence-religion/.

[4] For a discussion of Kurzweil’s views on duplicating ourselves, see Robin Phillips and Joshua Pauling, Are We All Cyborgs Now?: Reclaiming Our Humanity from the Machine (Basilian Media & Publishing, 2024), 149.

[5] Nick Bostrom, “Are We Living In a Computer Simulation?” Philosophical Quarterly 53 (211), 2003, 243–255.

[6] Elon Musk, cited in Rich McCormick, “Odds Are We’re Living in a Simulation, Says Elon Musk,” The Verge, June 2, 2016, https://www.theverge.com/2016/6/2/11837874/elon-musk-says-odds-living-in-simulation.

[7] Jason Koebler, “Elon Musk Says There’s a ‘One in Billions’ Chance Reality Is Not a Simulation,” Vice, June 2, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/8q854v/elon-musk-simulated-universe-hypothesis.

[8] Tad Friend, “Sam Altman’s Manifest Destiny,” The New Yorker, October 3, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/10/sam-altmans-manifest-destiny.

[9] Sam Altman, cited in Tad Friend, “Sam Altman’s Manifest Destiny,” The New Yorker, October 3, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/10/sam-altmans-manifest-destiny.

[10] “I think it's interesting how much sort of the Silicon Valley religion of the simulation has gotten close to, like, Brahman, and how little space there is between them, but from these very different directions. So, like, maybe that's what's going on. But if it is, like, physical reality as we understand I and all of the rules of the game are what we think they are, then there's something. I still think it's something very strange.” Sam Altman, Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI | Lex Fridman Podcast #367, 2023.

[11] Areesha Lodhi, "Never say goodbye’: Can AI bring the dead back to life?" Aljazeera (9 Aug 2024), https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/8/9/never-say-goodbye-can-ai-bring-the-dead-back-to-life

[12] See Robin Phillips and Joshua Pauling, Are We All Cyborgs Now?, pp. 444-46.

[13] Tristan Harris, “Can Myth Teach Us Anything About the Race to Build Artificial General Intelligence? With Josh Schrei,” January 18, 2024, http://www.humanetech.com/podcast/can-myth-teach-us-anything-about-the-race-to-build-artificial-general-intelligence-with-josh-schrei.

[14] C.S. Lewis, Screwtape Letters (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1942), 39–40.

There is a concept called an Egregore which I think fits perfectly on the peddling of transcendence (which has occurred from time immemorial).

And as regards culture, I would argue that one cannot actually understand the Bible or even be a cultural Christian without a knowledge of the Philosophy that is present throughout the Bible.

This is, I think, important as the transcendence people seem to want is a "physical" experience rather than a mental let alone a spiritual one.

Have you gotten a hold of Against the Machine yet?