The Mythic Vision of George MacDonald

In 1916, C.S. Lewis was seventeen and preparing to enter Oxford. One Saturday afternoon, as he stood on the Leatherhead train station waiting for the train that would take him back to his lodgings, he thought about “the glorious week end [sic] of reading” that awaited him. His attention turned naturally to the station’s bookstall.[1] On the shelf sat a curious looking volume, a secondhand copy of George MacDonald’s novel Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women.

Having journeyed through this station every week, Lewis had seen this book before yet never decided to buy it. That afternoon as he waited for the train, he picked up Phantastes and took a closer look. At this stage in his life, Lewis was “waist-deep in Romanticism”,[2] and this book seemed similar to other Romanticist literature he enjoyed. So he decided to buy it.

That evening Lewis opened Phantastes and entered into MacDonald’s imaginary landscape. Lewis was immediately haunted by the dream-like narrative in which ordinary life becomes transformed into the world of faerie. The story, he later reflected, “had about it a sort of cool, morning innocence, and also, quite unmistakably, a certain quality of Death, good Death.”[3]

The thick, moving, emotionally satisfying prose about the wanderings of Anodos contained all the qualities that had charmed him in other writers such as Malory, Spenser, and William Morris. Yet MacDonald’s story also had something more that he couldn’t quite put his finger on. “It is as if I were carried sleeping across the frontier, or as if I had died in the old country and could never remember how I came alive in the new.”[4] Lewis was later able to convey something of this feeling in his story The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe when the Pevensie children first hear the name of Aslan:

None of the children knew who Aslan was…but the moment the Beaver had spoken these words everyone felt quite different. Perhaps it has sometimes happened to you in a dream that someone says something which you don’t understand but in the dream it feels as if it had some enormous meaning…so beautiful that you remember it all your life.[5]

As Lewis went on to explore MacDonald’s other works, he felt that they contained some enormous significance. Yet there was one problem: at the time he was an atheist and MacDonald was a Christian. MacDonald’s theism was an annoyance to the young Lewis, who felt “it was a pity he had that bee in his bonnet about Christianity. He was good in spite of it.”[6] As Lewis grew and read more of MacDonald’s books, he came gradually to understand that the peculiar quality he encountered in Phantastes was not separate from MacDonald’s faith, but a result of it. “I did not yet know (and I was long in learning) the name of the new quality, the bright shadow, that rested on the travels of Anodos. I do now. It was Holiness.”[7]

It would be many years before Lewis’s intellect would follow. Nevertheless, the evening when he read Phantastes was the beginning of the slow journey that would eventually culminate in conversion to Christ. As Lewis put it in his autobiography, “That night my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptized; the rest of me, not unnaturally, took longer.”[8]

When Lewis did finally convert, he looked upon MacDonald as his spiritual master, saying, “I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself…. I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master.”[9]

But who was this man that had such a formative influence on C.S. Lewis? What was his vision of the world? And what was the peculiar quality of MacDonald’s mythmaking that gave his art this baptismal quality?

These are some questions this article will seek to answer. The first half will offer a sketch of MacDonald’s life, examining the unique experiences that led to his sacramental vision that has influenced so many thinkers and mythmakers since. The second half will explore key elements of MacDonald’s outlook, including his theory of imagination, his theology of beauty, and the re-enchanting quality of his mythmaking.

Fatherhood at the Core

George MacDonald was born outside Huntly, northern Scotland, on 10 December, 1824, the second son of his father’s seven children. His boyhood was a happy one, filled with rural fun and boyish adventures. His father, a musical hard-working manufacturer at the family’s small linen mill, was the most lasting influence on young George. A strict disciplinarian when obedience was in question, he turned a blind eye to his sons’ frequent mischief and escapades. “An almost perfect relationship with his father was the earthly root of all his wisdom,” C.S. Lewis observed. “From his own father, he said, he first learned that Fatherhood must be at the core of the universe.”[10]

George and his brothers spent much of their childhood outdoors, enjoying a close kinship with their natural surroundings. One might almost be tempted to describe George’s childhood as idyllic were it not for the fact that his mother died when he was eight. Though his mother’s death left a lasting impact on the sensitive child, the trauma was mitigated by the close bond he enjoyed with his father. It also helped when his father married again to a woman who proved to be the kindest of stepmothers.

The other great influence on George’s life was his paternal grandmother, Isabella Robertson MacDonald. After his mother died, Isabella took on a more prominent role in the lives of the MacDonald children. Isabella was a woman of great piety whom George always respected, yet she was terribly severe. As a young woman she had been responsible for the family joining the dissenting tradition, which embodied a particularly narrow Calvinism based on the Westminster Confession and highly influenced by thinkers like Jonathan Edwards and Thomas Boston. This outlook saw God as fundamentally wrathful, and while salvation was technically by grace, you could only know if you were among the elect through a strenuous program of good works. Many of the Scottish households at the time—with George’s boyhood home being no exception—had two books besides the Bible: Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Thomas Bostons’s Human Nature in Its Fourfold State. In the latter, the Scottish theologian argued that “God always acts like Himself – as no favors can be compared to His, so also His wrath and terrors are without a parallel.”[11] Boston added that God expresses his infinite wrath by bringing the joyful songs of heaven within hearing of the damned to show them what they are missing and thus to increase their torment, all the while laughing at their misery.

MacDonald scholar Kerry Dearborn tells how this outlook “produced a great sobriety in religion that distrusted the imagination, frowned on the arts (especially theater and music) and enforced a strict Sabbatarianism.”[12] Grandmother MacDonald famously burnt the violin belonging to George’s uncle, lest it lead the young men “beyond reach of the Divine Grace.”[13] When MacDonald later described a character based on his grandmother in his novel Robert Falconer, he wrote that “Frivolity…was in her eyes a vice; loud laughter almost a crime; cards, and novelles, as she called them, were such in her estimation, as to be beyond my powers of characterization.”[14] The village schoolmaster embodied this same outlook. An embittered man of almost legendary cruelty, his whip was rumored to have been responsible for the death of George’s younger brother.[15]

MacDonald’s actual family seems to have provided something of an antidote to the gloomier milieu. His immediate relations were well-educated and intellectual, while MacDonald enjoyed an upbringing that was “unusually rich in a family-sanctioned Western literary tradition.”[16] Similarly, his home parish, known as “Cowie’s church,” seems to have been comparatively healthy. The founder and namesake of the church, Rev. George Cowie, began to dwell more on love and grace during his later years, while MacDonald always looked back on his own boyhood pastor, John Hill, with fond memories, claiming him as a positive influence in his life.

These two strands—one gloomy and narrow, the other loving and intellectual—seem to have created a sense of dissonance in the young man that would later act as a catalyst for his own theological ministry.[17]

From Student to Tutor

MacDonald’s love of nature led to an interest in science, perhaps inspired by his close kinship with the natural world growing up among the beauties of the Scottish landscape. When he was sixteen he won a scholarship to study natural science at King’s College Aberdeen. During his university days, MacDonald was known to exhibit the same qualities that would forever characterize his life. His fellow student Robert Troup, who would later become the pastor of MacDonald’s boyhood parish, wrote, “He was studious, quiet, sensitive, imaginative, frank, open, speaking freely what he thought. His love of truth was intense, only equaled by his scorn of meanness, his purity and his moral courage.”[18]

During his college days MacDonald discovered works of German Romanticism. As a result of these books, his interest began to shift from science to the imagination, although he always retained a keen interest in the workings of the natural world. Despite his shifting interests, he continued with his scientific studies and graduated in April 1845 with a degree in chemistry and natural philosophy.

Originally MacDonald had intended to continue his scientific studies by going into chemistry. However, because he lacked funds to study under the best professors, he decided to take on work as a tutor while trying to discern the next step he should take. With the help of a family friend, he secured a position in London.

MacDonald’s student years gave rise to a gradually deepening crisis of faith. From an early age he intuited that his Heavenly Father could not be less loving and good than his earthly father, yet he struggled to reconcile this instinct with what he was taught about God from the prevailing theologies. He once reflected, “I have been familiar with the doctrines of the gospel from childhood, always knew and felt that I ought to be a Christian, and repeatedly began to pray, but as often grew weary and gave it up. The truths of Christianity had no life in my soul.”[19]

His reading of poetry and German romances had stirred his imagination with images of loveliness, while his close affinity with the natural world constantly fed his deep sensitivity for things of beauty.[20] But his sensitivity to art and beauty seemed at odds with the religious milieu of his upbringing, which he associated not with beauty but with ugliness. He no doubt spoke of his own childhood impressions when he later wrote that the fictional Robert Falconer felt that church was “weariness to every inch of flesh upon his bone.”[21] In his novel David Elginbrod he suggested sarcastically that the Scottish reformers had purposely attempted to create ugly models of worship:

One grand aim of the reformers of the Scottish ecclesiastical modes appears to have been to keep the worship pure and the worshippers sincere, by embodying the whole in the ugliest forms that could be associated with the name of Christianity.[22]

MacDonald became plagued by a dichotomy between beauty and faith, imagination and reason, religion and art. He was helped to bridge this gulf by reading the Bible, as well as Christian poets such as George Herbert and Henry Vaughan. The more he read, the more he saw that his religious and poetic sides were not in competition with each other but were actually complementary. Writing to his father in April 1847, he confessed, “One of my greatest difficulties in consenting to think of religion was that I thought I should have to give up my beautiful thoughts and love for the things God has made.”[23] He went on to say how reading the Bible was changing his perspective.

If [the gospel of Christ] be true, everything in the universe is glorious, except sin….I love my Bible more – I am always finding out something new in it – I seem to have had everything to learn over again…. But I find that the happiness springing from all things not in themselves sinful is much increased by religion. God is the God of the beautiful, Religion the love of the Beautiful, and Heaven the home of the Beautiful, Nature is tenfold brighter in the sun of Righteousness, and my love of Nature is more intense since I became a Christian – if indeed I am one.[24]

As this letter shows, MacDonald was coming to understand that his love for the beautiful was not separate from his relationship with Christ but integrally connected to it. In her book Baptized Imagination: The Theology of George MacDonald, Kerry Dearborn describes how “rather than viewing the imagination and the arts as satanic snares, MacDonald began to consider them as intimately connected with God’s good creation. He not only saw the imagination’s potential to harmonize with God’s creative ways, but also to convey something of God’s nature.”[25] MacDonald would later express this understanding in his book England’s Antiphon, where he posited what Dearborn termed “the basic interconnectedness of theology and poetry.”[26] As this harmony began to unfold in his thinking, MacDonald longed to point others to God, as well as to defend God against the libelous theologies that reduced Him to the level of a tyrant. Accordingly, MacDonald increasingly began to consider a career, not in science, but in the pulpit. The pulpit, he wrote, would not only provide opportunity “for personal advancement in holiness,” but “combines all wisdom and knowledge—all that is beautiful and true into one glorious whole.”[27]

During his years as a tutor in London, MacDonald made the acquaintance of Louisa Powell, daughter of a prosperous leather merchant. As the pair corresponded about spiritual topics and shared poetry, they developed a deep affection for one another. They were engaged to be married in 1848, the same year MacDonald entered a Congregationalist seminary in the city to prepare for the ministry.

From Pastor to Mythmaker to Novelist

With a background in science, some writers have puzzled why MacDonald suddenly decided to enter the ministry. He seems to have felt a genuine call to preach the message of God’s Fatherhood in opposition to what he took to be monstrous ideas about God that were circulating at the time. One such idea was a particular extreme theory of penal substitutionary atonement which turned God into a vindictive abuser not unlike his boyhood schoolmaster. Though MacDonald countered such theories with his message of God’s love, he never aligned himself with the growing movement of unitarian universalism, which bypassed the work of Christ and mitigated the reality of God’s wrath. MacDonald not only believed in God’s wrath but wrote about hell in vivid terms. Yet even God’s wrath is ultimately redemptive, being an expression of His love. God’s love, MacDonald taught, will not rest content until everything is put right.

When his seminary training was finished in 1850, MacDonald accepted a pulpit at Arundel, a small village in the South Downs of West Sussex. The same year he and Louisa were married. In his biography George MacDonald and His Wife, their oldest son Greville wrote, “Those were happy days indeed, with plenty to do among a people, simple, eager to learn, and very grateful.”[28] Unfortunately, these happy days were not to last. MacDonald’s ministry as a pastor was cut abruptly short in 1853 after he fell out of favor with the church’s wealthier patrons. Greville mentions two charges made against his father. The first charge was that he had “expressed his belief that some provision was made for the heathen after death.”[29] The second accusation is that he was “tainted with German theology,” a charge that may have originated from the fact that MacDonald had translated some poems of Novalis. These charges may have been a smokescreen for more interpersonal concerns: Greville speculates he roused indignation of the church’s wealthier patrons through his denunciation of mammon-worship and self-seeking,[30] while Daniel Gabelman suggests the church leaders may have sensed MacDonald’s divided loyalties as he was devoting substantial energy to poetry.[31]

At first the church’s patrons tried to induce MacDonald to abandon his pulpit by radically cutting his salary. This was a great hardship for him and Louisa, who now had an infant daughter to support. However, the inhabitants of the village made up for the shortfall by bringing the family fresh fruit, cabbages, potatoes, home-brewed beer and other simple gifts they could afford. Yet eventually the dissension grew too great and MacDonald was forced to resign to preserve the peace of the parish. The family moved to Manchester and then London, where MacDonald pursued his passion for teaching literature.[32] (Because of a lung condition, he was never able to permanently return to the cold, damp climate of his beloved Scotland, though he always remained a Scotsman at heart.) Despite MacDonald’s abilities, he had trouble finding permanent work, and it was sometimes challenging to know where the next meal would come from.

In an attempt to generate some income for his growing family, MacDonald decided to begin writing. His first publication, a wedding gift to Louisa when they married in 1855, was an epic poem composed some years earlier titled Within and Without. Although the work did not generate much income, it did bring him to the attention of Lady Byron, the widow of the poet Lord Byron. In the winter of 1856, Lady Byron decided to become MacDonald’s patron. This provided much-needed funding until MacDonald’s writing started generating sufficient income. Lady Byron also made it possible for the family to spend time in Algiers, Italy, where the change of climate greatly restored MacDonald’s health.

His next book, published in 1858, was the aforementioned Phantastes. Though this book suggested that his talents lay in the genre of fantasy, his publisher urged him to try his hand at novels. “If you would but write novels,” the publisher declared, “you would find all the publishers saving up to buy them of you! Nothing but fiction pays.”[33] But it would not be for another five years that MacDonald took this advice with the publication of David Elginbrod, a novel about a pious Scottish peasant and his daughter. For the rest of his career MacDonald wrote approximately one novel per year.

The success of David Elginbrod enabled MacDonald to find publishers for a number of short stories he had been writing for his children. This began with Adela Cathcart (1864), a novel that centers on the friends, family and doctor of a depressed young lady, Adela Cathcart. In an attempt to cheer Adela’s spirits and hasten her recovery, her doctor suggests they tell tales. At the end of the novel—after many wonderful stories—Adela recovers and marries the young doctor. One of the stories in Adela Cathcart is The Light Princess, a delightful tale about a princess without gravity, which explores themes of love, transformation, and sacrifice. His 1867 publication, Dealing with the Fairies, added to this growing corpus by including some of the stories that previously appeared in Adela Cathcart as well as some new ones, most notably The Golden Key.

These and the other stories MacDonald wrote are not merely fairy tales but can be considered mythic in the sense that they draw on primal symbols, imagery, significances and archetypes baked into the very fabric of reality. As a literary genre, this type of work is often described as mythopoeia which, in the words of Rolland Hein, references “stories that are composed in time, but which suggest (however dimly) something covert but eternally momentous.”[34] Or, to quote from Lewis, a myth, “gets under our skin, hits us at a level deeper than our thoughts or even our passions, troubles oldest certainties till all questions are reopened, and in general shocks us more fully awake than we are for most of our lives.”[35] Ironically, while MacDonald is most well-known today for his mythmaking, it was his novels that were most appreciated by his contemporaries.

As MacDonald was becoming more well-known, his novels offered hope of relieving the family’s financial burdens. Yet his reason for writing them was not entirely economic. His son Greville reflected on MacDonald’s “conviction that the world was so sorely in need of his message.”[36] It seems the novels provided MacDonald more scope for directly disseminating his vision. While they include long sermons and theological conversations, their true pedagogical quality lies in the characters themselves. Each novel typically centers on a person who goes on a journey of inner transformation. “Aided by a Virgilian guide,” writes Daniel Gabelman, “this inner transformation is usually brought about by some combination of emotional or physical suffering and increased sensitivity to both natural and literary beauty.”[37] By the end of the novel, however, the reader will also likely experience transformation, as the protagonists demonstrate what it means to breathe grace in the midst of conflict, to give charitably in the midst of poverty, to model Christ’s love in the midst of suspicion and mistrust, to bring hope in the midst of suffering, and to live according to Christ’s commands in the midst of hypocrisy, compromise, self-centeredness, and distorted theologies.

Though the novels were received with increasing enthusiasm by the public, MacDonald still struggled to put food on the table for his growing family. Thus, he frequently found it necessary to take a variety of miscellaneous jobs to supplement the income from his writing. (In part these continued financial struggles were due to the existence of so many pirated versions of his books. It was not until the 1870s that MacDonald began to receive payments from some of the American editions.) The jobs he took included lecturing in science and English literature, editing a magazine for children, and even working as a professional dramatist with other members of his family. He also spent time substitute preaching but never accepted any money for it. It was not until his career was at its height in the 1870s that the family was finally free from financial hardships.

By 1872 MacDonald had developed such a reputation that he was able to undertake a tour on the American lecture circuit. Taking Louisa and Greville with him, they journeyed in the United States for nine months over the winter of 1872-73, travelling as far West as Chicago and as far North as Canada. MacDonald was an instant hit for the Americans as he lectured on Dante, Shakespeare, Chaucer, Milton, and the romantic poets. But the Americans derived particular satisfaction from hearing the Scotsman discourse on Robert Burns. Sometimes his audiences would reach into the thousands. Famous American writers paid him homage, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Mark Twain. Despite the accolades, the family’s greatest joy during the trip was meeting with the ordinary people who had been inspired to deeper faith and obedience through the novels.

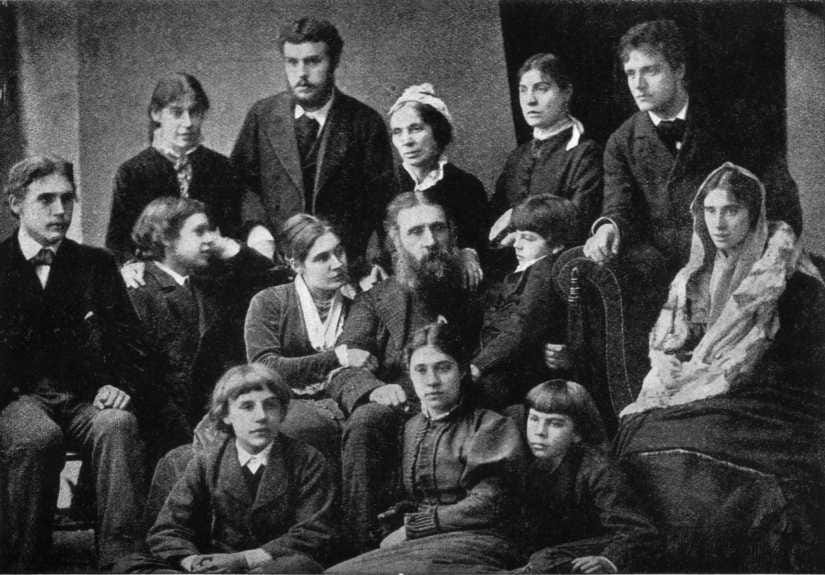

The MacDonald Family

Though MacDonald could be serious at times, haunted with melancholy moods, Greville recounts how he maintained a jovial and humorous atmosphere for his family. The MacDonald home was always lively, full of love, games (charades was one of his favorites), drama, music, and—when they could afford it—generous hospitality to other families. Despite their poverty, George and Louisa did what they could to give their children a spiritually rich and joyful upbringing. Through their parents, the MacDonald children came to know many of the leading literary figures of late Victorian England, including Charles Kingsley, Frederick Denison Maurice, John Ruskin and Charles Dodgson. Dodgson, whose pen name was ‘Lewis Carroll’, first tested his draft manuscript Alice’s Adventures Underground on the MacDonald children when trying to decide whether it was good enough to publish.

When their children were grown, George and Louisa continued to maintain a deep concern for each of their spiritual lives. Even after they had moved away from home, some of the children would write to ask their father questions about God and life. In one letter, answering questions that his daughter ‘Elfie’ (the nickname for his daughter Mary) had asked him about love, he ended by replying, “Ask me anything you like, and I will try to answer you – if I know the answer. For this is one of the most important things I have to do in the world.” Elsewhere in the same letter he encouraged Elfie by reminding her that

God is so beautiful, and so patient, and so loving, and so generous that he is the heart & soul & rock of every love & every kindness & every gladness in the world. All the beauty in the world & in the hearts of men, all the painting all the poetry all the music, all the architecture comes out of his heart first. He is so loveable that no heart can know how loveable he is – can only know in part. When the best loves God best, he does not love him nearly as he deserves, or as he will love him in time.[38]

Final Days

One of MacDonald’s final books, Lilith, drew on the fruits of his mature imagination. Filled with what Greville called “symbolic allusiveness,”[39] the narrative is haunting and obscure, dealing with ultimate themes of death and redemption. While Lilith has proved to be one of MacDonald’s most-discussed work, Louisa was troubled by its dark imagery. MacDonald began to doubt his literary abilities and it was only after Greville read the manuscript and gave a positive verdict that husband and wife agreed to let the book proceed.[40]

Around the turn of the century (the exact date is uncertain), MacDonald lost the ability to speak, likely because of a stroke. He spent the last five years of his life in virtual silence, peacefully waiting to meet his Master. To the very end, his family tenderly cared for him, especially after Louisa passed away in 1902. The death of Louisa came as a great blow to MacDonald, and though he couldn’t speak a word, he wept bitterly after the news was communicated to him.

The following words, written in 1880, shortly after the deaths of two of his children, describe the feeling of expectation that must have also given him peace during his silent vigil as he waited to meet His maker and be reunited with his wife:

Yet hints come to me from the realm unknown;

Airs drift across the twilight border-land,

Odoured with life; and, as from some far strand

Sea-murmured, whispers to my heart are blown

That fill me with a joy I cannot speak.[41]

George MacDonald’s Legacy

MacDonald left behind over 50 books, representing the extraordinary breadth of his interests. His corpus includes poetry, literary criticism, novels, fantasies, essays, plays, and theology. Until the end of the nineteenth century, he was a household name in both the UK and the US, where he enjoyed a popularity that was perhaps only rivaled by Dickens and Scott. Yet this popularity was not to last. Although short stories like The Princess and the Goblin and The Light Princess have remained enduring classics, most of his other writings fell into neglect. Today, none of the anthologies of Victorian literature even mention MacDonald’s name.[42]

The rising popularity of C.S. Lewis among evangelicals in the latter 20th century helped resuscitate MacDonald’s legacy, while in the early 1980s, the novels became bestsellers again after my father, Michael Phillips, edited eighteen of them for Bethany House Publishers. Meanwhile, many are now rediscovering MacDonald through other authors he influenced besides Lewis, including John Ruskin, Lewis Carroll, Frances Hodgson Burnett, G.K. Chesterton, James Barrie, E. Nesbit, W.B. Yeats, H.G. Wells, T.S. Eliot, J.R.R. Tolkien, Maurice Sendak, W.H. Auden, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Madeleine L'Engle, Ursula Le Guin, Frederick Buechner, Sally Vickers, and Jeffrey Overstreet. Ultimately, however, MacDonald’s influence stretches beyond the specific individuals he touched, for he helped pioneer what Marion Lochhead has called “a renaissance of wonder in books for children.”[43] He also brought respectability to the genre of the adult fantasy, laying groundwork for what would later reach fruition in Tolkien’s Masterpiece The Lord of the Rings.

C.S. Lewis’s own words about MacDonald’s three-volume Unspoken Sermons remain the testimony of countless others who have drunk deeply from the wells of MacDonald’s spiritual imagination:

My own debt to this book is almost as great as one man can owe to another: and nearly all serious inquirers to whom I have introduced it acknowledge that it has given them great help—sometimes indispensable help toward the very acceptance of the Christian faith.[44]

But how and why did MacDonald help so many to accept the Christian faith? He was not a typical apologist in the sense of marshalling arguments for the truth of Christianity; rather, his writing did something more valuable: he showed the beauty of the Christian story, articulating a vision of re-enchantment that was as counter-cultural in his day as in our own. He aimed to show, not simply that the Christian story is true, but that it is attractive. Let’s unpack this more deeply.

Making Goodness Attractive

MacDonald’s spiritual vision retained the strong emphasis on good works that was a prominent feature of the Scottish non-conformists. Yet unlike the dour moralism of his grandmother, he showed that obedience to Christ is lovely. While the characters in his novels constantly remind us that nothing is as important as a person doing his or her duty in the next five minutes, they also show that there is nothing quite so exciting. MacDonald aimed to educate his readers not simply about the rightness of a moral life, but to demonstrate the attractiveness of it. In this he paved the way for apologists like G.K. Chesterton and Dorothy Sayers who were likewise concerned to defend Christian morality not so much from the accusation of falsehood as from the charge of tedium.

Here MacDonald echoes with abiding quest of ethics, namely the project of moral formation through the reordering of affection. In ancient ethical reflection, present everywhere from the Hebrew Wisdom Literature to Plato to St. Augustine, being a virtuous man or woman involves more than merely doing what is right; rather, a truly virtuous human being is actually attracted to the good. While ancient thinkers appropriately emphasized the importance of habitus in forming the affections, they did not always appreciate the role imagination can also play. Plato famously banned poets from his hypothetical utopia while many Christians in the Greek monastic tradition took an ambivalent view of the imagination and fantasy literature. MacDonald expands the toolkit of resources available for reordering the affection, giving the imagination an elevated role in moral formation. He believed that by appealing to the imagination, the skilled artist could reach the individual at the level of pathos, provoking an emotional sympathy with the good far more effectively than what can be achieved by mere didactic instruction or legalistic moralism.[45] As MacDonald put it in his lecture, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture,”

Seek not that your sons and your daughters should not see visions, should not dream dreams; seek that they should see true visions, that they should dream noble dreams. Such out-going of the imagination is one with aspiration, and will do more to elevate above what is low and vile than all possible inculcations of morality….

Few, in this world, will ever be able to utter what they feel. Fewer still will be able to utter it in forms of their own. Nor is it necessary that there should be many such. But it is necessary that all should feel. It is necessary that all should understand and imagine the good; that all should begin, at least, to follow and find out God.[46]

Rightly-ordered feeling thus lay at the heart of MacDonald’s ethics (a point I have developed elsewhere), while imagination remained a crucial tool for achieving elevated spiritual feelings and deeper understanding. Yet it would be a mistake to view MacDonald’s imaginative works as mere pedagogical tools for a moralizing agenda, as if a fairy tale is simply a husk that is necessary for delivering the spiritual kernel within. Here we can learn from Lewis: when gathering his Anthology of quotes from MacDonald, Lewis did not try to extract detachable merits from the fairy stories like he did from the novels and sermons because, having the quality of mythopoeic art, it is in the story itself wherein the value lies: “The meaning, the suggestion, the radiance, is incarnate in the whole story: it is only by chance that you find any detachable merits.”[47] MacDonald would have agreed with Lewis for, useful as fairy tales are, their value can never be limited to mere pragmatism. Nor can fairy tales be reduced to an explainable meaning.[48] Fantasy reorders us not through mere allegory,[49] nor through a text having a fixed point or message,[50] nor by providing fodder for the intellect,[51] but through reaching our hearts at the level of feeling. Just as nature “rouses the something deeper than the understanding,”[52] MacDonald sought “to move by suggestion.”[53] This is exactly what Phantastes did for Lewis long before his mind caught up to his baptized imagination.

Ultimately, MacDonald understood that a rightly ordered imagination aligns our hearts with the divine harmonies already present in creation yet obscured through long familiarity:

For the end of imagination is harmony. A right imagination, being the reflex of the creation, will fall in with the divine order of things as the highest form of its own operation; “will tune its instrument here at the door” to the divine harmonies within.[54]

In my reading of MacDonald, it is his fantasy works that achieve this retuning most effectively. While his fairy tales take us into dream-worlds full of strange creatures and fantastic occurrences, they are not escapist, for they help us view the real world, and our role in it, with greater clarity, insight and wonder.

While his fairy tales take us into dream-worlds full of strange creatures and fantastic occurrences, they are not escapist, for they help us view the real world, and our role in it, with greater clarity, insight and wonder.

Through the eyes of the imagination, we come in harmony with the true nature of reality, achieving what MacDonald called “an inward oneness with the laws of the universe.”[55] We come to rediscover the fairy tale at the heart of reality. After accompanying Mr. Vane through the mysterious landscape of Lilith, or following Diamond’s travels with Lady North Wind in At the Back of the North Wind, or journeying with Curdie to Gwyntystorm in The Princess and Curdie, we begin to see the mystery and enchantment that suffuses all of life. We begin to feel that the world of Faerie, as MacDonald liked to spell it, has invaded the world of men or, as Chesterton put it when writing about MacDonald, that “the fairy-tale was the inside of the ordinary story and not the outside.”[56] His mythic vision, encapsulated in his fantastic works, invites us to see the world not primarily as facts but as a wonderful story that we are participating in and contributing to.

This is no doubt part of the reason MacDonald’s works helped to nudge the young Lewis away from materialism and atheism. “The quality which had enchanted me in his imaginative works,” Lewis reflected, “turned out to be the quality of the real universe, the divine, magical, terrifying and ecstatic reality in which we all live.”[57] MacDonald himself articulated something like this in his essay “A Sketch of Individual Development,” where he argued that our world is every bit as magical, wonderful, and enchanted as the world of fairyland, though we need the eyes of our imagination open to perceive this. In the same work, MacDonald writes movingly about what happens when a person’s spiritual vision is opened and “the world begins to come alive around him.”

He begins to feel that the stars are strange, that the moon is sad, that the sunrise is mighty. He begins to see in them all the something men call beauty. He will lie on the sunny bank and gaze into the blue heaven till his soul seems to float abroad and mingle with the infinite made visible, with the boundless condensed into colour and shape. The rush of the water through the still twilight, under the faint gleam of the exhausted west, makes in his ears a melody he is almost aware he cannot understand.[58]

Here MacDonald was on common ground with nineteenth century Romantics like Wordsworth, who also saw the world pervaded with spirituality. Yet MacDonald goes one step further. He showed that it is goodness which infuses our world with meaning and makes it beautiful. In contrast to the prosaic moralism of the tradition represented by his grandmother (which drained all beauty out of goodness), and in contrast to the more subjective strain of Romanticism (which untethered beauty from its foundations in objective goodness), MacDonald showed that beauty and objective goodness cannot be separated. It is precisely this that makes his works so spiritually potent. “I should have been shocked in my teens” wrote C.S. Lewis, “if anyone had told me that what I learned to love in Phantastes was goodness. But now that I know, I see there was no deception. The deception is all the other way round – in that prosaic moralism which confines goodness to the region of Law and Duty, which never lets us feel in our face the sweet air blowing from ‘the land of righteousness,’ never reveals that elusive Form which if once seen must inevitably be desired with all but sensuous desire.”[59]

But if MacDonald’s thought served as an antidote to the gloomy Christianity of his own day, his vision is equally resourceful against hedonistic forms of Christianity common in our own. Under the guise of making Christianity attractive and “seeker-sensitive,” contemporary religion often accommodates itself to mere worldliness. Significantly, MacDonald aimed to show that it is real goodness (in all its asceticism, self-denial and ethical rigor) that must be seen as attractive and beautiful. Yet the attractiveness of goodness can be obscured through sin, which disorders our affections through the lure of counterfeit beauties, leading to a revulsion against the good. Aversion against goodness ultimately results in hell, a condition in which even God’s love becomes a torment to the sinner clinging to egotism.[60] MacDonald portrayed something of this in his fairy tale The Wise Woman, in which the loving tutelage of a wise woman is initially perceived as hateful to two spoiled girls. Significantly, however, the woman’s discipline works not merely a change in outward behavior, but a change in inner disposition – a reordering of desire so the girls ultimately find virtue to be pleasing. Art and beauty, no less than discipline and good habits, can serve this same function in bringing our dispositions into alignment with the Good. This, in turn, gives the imagination a central, even inescapable, role in the spiritual life, because of the way it can penetrate straight to the heart. This will become clearer if look closer at MacDonald’s theory of imagination.

The Inescapability of Imagination

MacDonald lived at a time when, much like our own, the imagination was misused, misunderstood, neglected, perverted, or feared. Victorians had many factors working against the imagination, from the nascent scientism that would later blossom into materialistic reductionism, to the Enlightenment rationalism embodied in people like Dickens’ Mr. Gradgrind, to the mechanical logic of industrial society with the dehumanizing routines of the factory. For many Victorians, imagination was perceived as an irrelevant distraction, while others looked on it—like their fixation with the innocence of childhood—as a means for escaping the grim realities of a cruel world. But MacDonald understood the imagination as providing, not an escape from the real world, but a kind of higher vision that allowed one to grasp more deeply the true nature of reality.

MacDonald articulated this doctrine of imagination throughout his works, but nowhere more powerfully than his lecture already referenced, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture.” The talk, which he delivered and published it numerous different places from at least 1865 to the early 1890s, shows MacDonald’s awareness of how imagination can be misused. For example, he describes how imagination can be put to the service of mere fancy. He also interacts with a hypothetical objector who asserts that all we need for understanding the world is knowledge of scientific laws. MacDonald’s answer to both these extremes is that imagination is inescapable; hence, if we do not cultivate a rightly ordered imagination (what he called the “prophetic imagination”), then we will be victim to disordered visions.

Anticipating thinkers like Lewis and Barfield, MacDonald’s argument is that all reality is apprehended imaginatively and symbolically, even in realms like science where the imaginative element may be camouflaged. As Chris Brawley reminds us, “In order for the eternal to be perceived through the temporal, an act of imagination is required.”[61] Indeed, as carnate creatures, we can only know and experience spirit in an incarnated form, via images and symbols. Consequently, all communication and thought depends, however tacitly, on imagination. As Annie Crawford put it,

There is no language or meaning without the symbols and images and metaphors that the imagination connects to our mere written or spoken words…The imagination is that mental faculty that mediates between the senses and the intellect by putting our raw sensory experience into a form which the intellect can understand and act on.[62]

Rejecting the idea that there can be a zone of imaginative neutrality, MacDonald believed his fantasy works were just as spiritual as his sermons. This is why, in the passage cited earlier, he enjoined teachers not to try to eradicate dreams and visions, but to cultivate noble dreams and visions, that is, a rightly ordered imagination. For MacDonald, the stakes here were very high, for if we do not recognize the imaginative element in all of life and work, and if we do not healthfully nurture the innate longing for beauty, transcendence and enchantment, then our longings will inevitably be colonized by subversive forces. If the imagination “be not occupied with the beautiful, she will be occupied by the pleasant; that which goes not out to worship, will remain at home to be sensual.”[63] Dostoevsky’s observation might equally have been made by MacDonald: “The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of men.”[64]

If we do not recognize the imaginative element in all of life and work, and if we do not healthfully nurture the innate longing for beauty, transcendence and enchantment, then our longings will inevitably be colonized by subversive forces.

The idea that imagination is unavoidable is particularly potent for our own day, as we live in the twilight of Modernism with its antitheses between fact vs. value, head vs. heart, reason vs. feeling, the spiritual vs. the imaginative, etc. MacDonald rejected this web of dualisms, believing that “The highest imagination and the lowliest common sense are always on one side.”[65] What he had once hoped to achieve in the ministry (believing it would “[combine] all that is beautiful and true into one glorious whole,”) he came to see as fulfilled in the imagination, which unites seemingly disparate elements into an integrated vision. Thus, the ultimate choice we face is not whether to be imaginative, but whether our imaginations will be healthy or disordered.

That evil may spring from the imagination, as from everything except the perfect love of God, cannot be denied. But infinitely worse evils would be the result of its absence. Selfishness, avarice, sensuality, cruelty, would flourish tenfold; and the power of Satan would be well established ere some children had begun to choose. Those who would quell the apparently lawless tossing of the spirit, called the youthful imagination, would suppress all that is to grow out of it. They fear the enthusiasm they never felt; and instead of cherishing this divine thing, instead of giving it room and air for healthful growth, they would crush and confine it — with but one result of their victorious endeavours — imposthume, fever, and corruption. And the disastrous consequences would soon appear in the intellect likewise which they worship. Kill that whence spring the crude fancies and wild day-dreams of the young, and you will never lead them beyond dull facts — dull because their relations to each other, and the one life that works in them all, must remain undiscovered.[66]

Reconnecting Goodness, Truth and Beauty

Beauty and truth are integrally bonded. In fact, in classical metaphysics, the transcendental attributes of being (truth, goodness, beauty, and unity) were understood to be convertible with one another. Yet while beauty is inseparably connected with truth, we are not. Consequently, sometimes beauty rouses us where the truth falls silent on our ears. The great Russian novelist, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, understood this, observing as follows in his 1970 Nobel Price Lecture.

There is, however, a certain peculiarity in the essence of beauty, a peculiarity in the status of art: namely, the convincingness of a true work of art is completely irrefutable and it forces even an opposing heart to surrender.... So perhaps that ancient trinity of Truth, Goodness and Beauty is not simply an empty, faded formula as we thought in the days of our self-confident, materialistic youth? If the tops of these three trees converge, as the scholars maintained, but the too blatant, too direct stems of Truth and Goodness are crushed, cut down, not allowed through – then perhaps the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected stems of Beauty will push through and soar TO THAT VERY SAME PLACE, and in so doing will fulfil the work of all three?...Those works of art which have scooped up the truth and presented it to us as a living force – they take hold of us, compel us, and nobody ever, not even in ages to come, will appear to refute them.”[67]

MacDonald also understood this; consequently, whether he was writing fairy tales or sermons, novels or poetry, he always aimed to clothe truth in beauty, to educate the aesthetic faculties and not merely the mind. In this he anticipated the 21st century with its wave of interest in “imaginative apologetics,” “cultural apologetics,” and “literary apologetics,” all of which seek to move beyond modernist models of persuasion by appealing to the whole person.[68]

“My chief aim,” he wrote in England’s Antiphon, “will be the heart, seeing that, although there is no dividing of the one from the other, the heart can do far more for the intellect than the intellect can do for the heart.”[69] The way to reach the heart, in turn, was through beauty. Yet MacDonald never presented beauty as an end in itself. Given that beauty has its home in the divine Goodness and Truth, she must remain connected to her sister transcendentals to retain coherence. In failing to discern God’s goodness behind beauty, many of the English Romantic poets never went far enough. John Keats’ poem ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ expressed widely popular sentiments:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” - that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.[70]

By contrast, MacDonald taught that there was something more we needed to know, namely that there is an ultimate Source from which all beauty springs. Though MacDonald did not conflate truth and beauty as Keats seemed to do, he agreed that they were inseparable and spoke of hoping “for endless forms of beauty informed of truth.”[71] The connection between truth and beauty arose by virtue of each having their home in “God’s heart… the fount of beauty.”[72] He took up this same theme in many of the essays collected together in A Dish of Orts. For example, in an essay on Wordsworth’s poetry he wrote,

Let us go further; and, looking at beauty, believe that God is the first of artists; that he has put beauty into nature, knowing how it will affect us, and intending that it should so affect us; that he has embodied his own grand thoughts thus that we might see them and be glad.[73]

As this suggests, beauty can only be properly understood when organically integrated with goodness and truth. But truth must also be understood correctly. Most of MacDonald’s contemporaries were not Romantics but held to modalities more akin to enlightenment rationalism; accordingly, truth was understood in reference to the reductionism of empiricist epistemology or the cold logic of utilitarianism. MacDonald offered a much more holistic understanding of truth, in addition to reuniting truth with her sisters, beauty and goodness. Truth without beauty was always regretful to MacDonald, since “beauty is the only stuff in which Truth can be clothed.”[74] Yet MacDonald, like his friend Ruskin, would also reject the Aesthetic Movement which left beauty bereft of truth. In one of his sonnets, MacDonald spoke of the unfortunate disconnection between beauty and truth among those who cared little for the latter:

From the beginning good and fair are one,

But men the beauty from the truth will part,

And, though the truth is ever beauty's heart,

After the beauty will, short-breathed, run,

And the indwelling truth deny and shun.[75]

This interconnectedness of beauty and truth is central to MacDonald’s literary theory. When discussing the fantasy genre, he argued that there must be a confluence of beauty and truth. “The beauty may be plainer in it than the truth,” he observed, “but without the truth the beauty could not be, and the fairytale would give no delight.”[76] By this he did not mean that a tale must have a “message” (on the contrary, he found allegories to be a weariness to the soul) but that stories must be in tune with the divine harmonies of the world.

While MacDonald saw goodness, truth and beauty as intimately related, he also recognized that in a fallen world beauty can sometimes distract us from fully imbibing what is true and good. Thus, in the rest of the sonnet just cited, he goes on to describe how God's words came to man “in common speech, not art” and that

For Truth's sake even [beauty's] forms thou didst disown:

Ere, the love of beauty, truth shall fail.

In some of MacDonald’s fairy tales he explores what happens when beauty becomes disconnected from goodness and truth, or when we make an idol out of beauty by mistaking shadow for reality, image for prototype. The character of Lilith in his book Lilith, or the Alder tree in Phantastes give a stark portrayal of beauty as disengaged from goodness and truth.

The indivisibility in the triumvirate of goodness, truth and beauty meant that to separate any of these three was to do violence to the others. In this MacDonald anticipated the thought of the 20th century Roman Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, who wrote,

We no longer dare to believe in beauty and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it. Our situation today shows that beauty demands for itself at least as much courage and decision as do truth and goodness, and she will not allow herself to be separated and banned from her two sisters without taking them along with herself in an act of mysterious vengeance.[77]

Such mysterious vengeance occurred when late 19th century art and literature trailed off into obscuration and perversity, until finally culminating in the Decadent Movement. With prophetic insight, MacDonald had inadvertently predicted this in his essay, “A Sketch of Individual Development” when he had observed, “The soul departs from the face of beauty, when the eye begins to doubt if there be any soul behind it.”[78] This understanding that beauty is rooted in God distinguished MacDonald from the cult of beauty-worship that became a feature within some strains of Late Romanticism. MacDonald understood that beauty, when severed from God’s truth and goodness, can disorder the heart in a kind of reverse-catechesis. The solution, he taught, is to move from shadow to reality.

Shadows were important throughout MacDonald’s corpus, yet to grasp their significance we need to understand something of the qualified Neoplatonism he was working with.[79] The basic framework goes something like this. The beauty we encounter on earth is a reflection of the primal beauty of God; consequently, all created beauty achieves coherence only by participating in God, the archetype of goodness, truth, and beauty. Yet while the beautiful things of this earth possess true beauty in and of themselves (and not in a merely instrumental sense), they do not possess final and complete beauty. Rather, the beautiful things of earth are shadows of that original beauty from which they derive and towards which they point. When received properly, terrestrial beauties kindle in us longings for something beyond the scope of earthly experience in the present age. To reach our proper telos and truly flourish, however, mankind must ascend from icon to prototype, shadow to reality.[80] This ascent sometimes involves leaving behind the shadows, however beautiful they may be, to willingly embrace the seeming detour of asceticism of sacrifice and pedestrian obedience. As C.S. Lewis would later put it, “The road to the promised land runs past Sinai.”[81] In The Golden Key, Tangle and Mossy were vouchsafed a heavenly vision in a watery sea of shadows, yet they were only able to reach the country from which the shadows came by turning away from the shadows to embark on an ascetical journey that would ultimately culminate in aging and—by implication—death. Yet, as we shall see in the next section, even shadows have a valued place in God’s creation, since the proper pursuit of heaven—what MacDonald called “the country from which the shadows come”—leads not to a denigration of earthly life (as in certain variants of Neoplatonism), but a transfiguration of it.

A Theology of Re-Enchantment

“The cultural air we breathe fuels the hunger for the extraordinary,” observes Julie Canlis.[82] Indeed, one of the reasons so many people become victims of disordered entertainment—from drugs to horror movies to thrill-seeking in extreme sports—is that we are searching for wonder in all the wrong places, having lost the ability to find it in the ordinary. This inability to perceive wonder in ordinary things comes as the consequence of a long process of disenchantment that Charles Taylor and others have described as a hallmark of the modern age.

MacDonald was dealing with the same disenchantment, as Victorian England saw a confluence of scientific materialism and enlightened rationalism. Disenchanted nature became, in Tennyson’s words, “red in tooth and claw.” For MacDonald, on the other hand, nature was charged with divine resonances. He continually countered disenchantment with a sacramental ontology that drew heavily on the Middle Ages, especially the medieval notion that externals of our world act as outward signs of inward spiritual graces.

It is true that we do not often find MacDonald employing explicitly sacramental terminology, a fact that is hardly surprising given his involvement in the dissenting church. Yet after converting to Anglicanism in his early forties, his writing took on a more directly eucharistic tone. For example, in 1870 he used Holy Communion as a symbol for the transfiguration of all things.

There is a glad significance in the fact that our Lord’s first miracle was this turning of water into wine. It is a true symbol of what he has done for the world in glorifying all things. With his divine alchemy he turns not only water into wine, but common things into radiant mysteries, yea, every meal into a eucharist, and the jaws of the sepulchre into an outgoing gate…. From all that is thus low and wretched, incapable and fearful, he who made the water into wine delivers men, revealing heaven around them, God in all things, truth in every instinct, evil withering and hope springing even in the path of the destroyer.[83]

While passages like this indicate that MacDonald viewed the entire world through a eucharistic lens, he never lapsed into a reductionism common among many Protestants of his day who, treating everything as sacred in a general sense, ended up treating nothing as sacred in a particular sense.[84] On the contrary, he maintained an acute awareness for how specific things and actions become pregnant with meaning, bearing a symbolic significance that both illumines and transcends the particular. We see this in the how the symbolism of baptism is important throughout his corpus. In The Light Princess, it is only in water—a type of baptism—that the heroine can gain her normal weight, leading to emotional and spiritual rebirth. The symbolism of baptism is also a motif running throughout The Princess and Goblin.[85] In The Golden Key, it is in the watery expanse of a lake that Tangle and Mossy catch a glimpse of heaven through the shadows that play in the water’s surface. Thus are their imaginations captivated by the possibility that there is a world behind the shadows.[86]

After sitting for a while, each, looking up, saw the other in tears: they were each longing after the country whence the shadows fell.

“We must find the country from which the shadows come,” said Mossy.

“We must, dear Mossy,” responded Tangle.

In MacDonald’s realistic novels, water is similarly described as a ladder by which we can ascend to the heavenly. In Castle Warlock, for example, the boy Cosmo reflects on the ever-receding origins of water until finally, as a young man, “he saw in God the one only origin, the fountain of fountains, the Father of all lights—that is, of all things, and all true thoughts.”[87] As in the New Testament,[88] so in MacDonald’s stories, baptism by water is integrally connected with the symbolism of death, judgment, and the pain of new birth. His characters often battle against deadly floods, while the floodwaters of judgment help restore order at the end of The Princess and Goblin. In The Light Princess, redemption occurs in the waters of death as the prince faces drowning to undo the curse placed on the princess. With good reason did Lewis say that MacDonald “baptized” his imagination, since the imagery of baptism by water plays such a central part in MacDonald’s symbolic vision.

It was this sacramental outlook that resonated with G.K. Chesterton more than anything else about MacDonald’s works. In his book Saint Francis of Assisi, Chesterton noted that the saint “was a poet whose whole life was a poem. He was not so much a minstrel merely singing his own songs as a dramatist capable of acting the whole of his own play.”[89] Chesterton might just as well have been talking about MacDonald. When he came to write the introduction to George MacDonald and His Wife, Chesterton referred to MacDonald as the “St. Francis of Aberdeen.”[90] MacDonald, like Saint Francis, was gifted with the ability to see “the same sort of halo round every flower and bird.”[91] This sacramental vision represented what Scottish religion would have been if it had continued within the template of Scottish medieval poetry – a religion which, to quote again from Chesterton, “competed with the beauty and vividness of the passions, which did not let the devil have all the bright colours, which fought glory with glory and flame with flame.”[92]

Far from being escapist, this mythic vision enables us to penetrate to the very fabric of reality, disclosing a divine order obscured through long familiarity. That is why the mythic imagination is ultimately prophetic, offering an apocalypse (lit. “unveiling”) whereby we are realigned to see the world in its true light. Art achieves this realignment through rescuing ordinary life from the illusion of the humdrum and tedious. Art is separate from everyday life, only to bring us back to the common world with fresh eyes ready to see the wonder in the ordinary.[93] As one of MacDonald’s characters in Phantastes explains,

But is it not rather that art rescues nature from the weary and sated regards of our senses, and the degrading injustice of our anxious every-day life, and, appealing to the imagination, which dwells apart, reveals nature in some degree as she really is, and as she represents herself to the eye of the child, whose every-day life, fearless and unambitious, meets the true import of the wonder-teeming world around him and rejoices therein without questioning?[94]

Ultimately MacDonald’s mythic vision kindles in our hearts a vision for our true homeland so that we can join Tangle and Mossy in exclaiming, “We must find the country from whence the shadows come.” Far from entailing a gnostic escapism that would problematize the material world, however, this quest for the true homeland elevates earthly existence; longing for heaven transfigures worldly experience.

MacDonald’s mythic vision kindles in our hearts a vision for our true homeland so that we can join Tangle and Mossy in exclaiming, “We must find the country from whence the shadows come.” Far from entailing a gnostic escapism that would problematize the material world, however, this quest for the true homeland elevates earthly existence; longing for heaven transfigures worldly experience.

Perhaps the clearest statement of this comes in “The Shadows,” a short story that MacDonald likely composed the same summer he wrote Phantastes, and first appeared in Adela Cathcart. Here MacDonald inverts Plato’s cave allegory through the tale of Ralph Rinkelmann. Rinkelmann is vouchsafed a vision of shadows that is reminiscent of the prisoners in Plato’s cave. “The dancing shadows in his room seemed to him odder and more inexplicable than ever. The whole chamber was full of mystery.”[95] Yet, in a move that Daniel Gabelman refers to as “a direct criticism of Plato's allegorical vision,”[96] MacDonald suggests that the truth of Rinkelmann’s vision depends on the extent to which it transfigures the ordinary realm, disclosing the splendor in the common.

This made it the more likely that he had seen a true vision; for, instead of making common things look common place, as a false vision would have done, it made common things disclose the wonderful that was in them.

These words incapsulate the true spirit of MacDonald’s mythic vision. He longed to liberate us from the clouded vision that sees common things as “commonplace.” His fairies and magical realms take us away from this world only to send us back with a fresh wonder, ready to perceive the extraordinary in the ordinary, to recognize the sacred in the everyday, and to rediscover the beauty in the familiar and homely.

Postscript

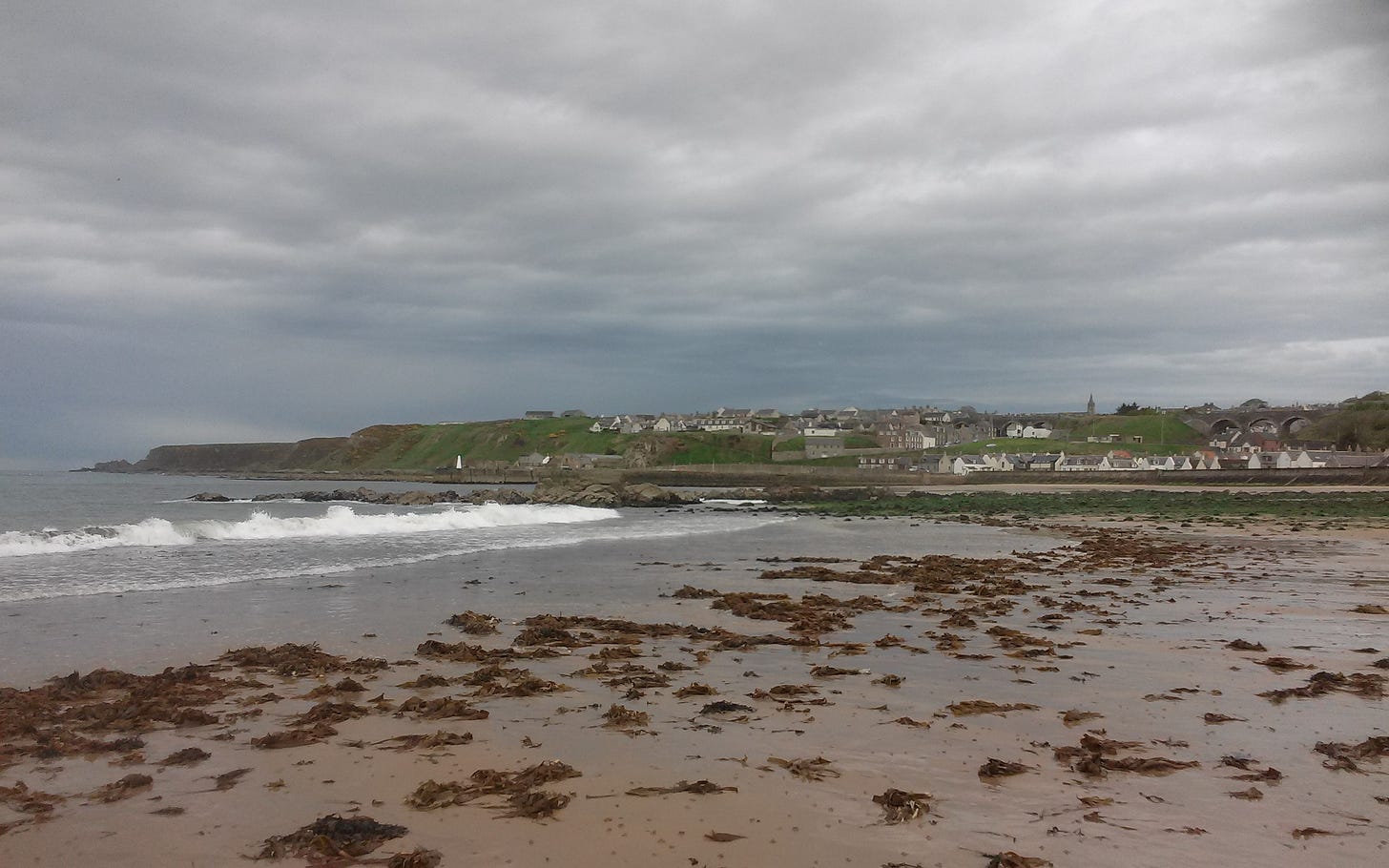

In 2015 I visited areas of Scotland associated with MacDonald (the third of four MacDonald pilgrimages throughout the fifty years) and I took these pictures during walks.

Further Reading

[1] C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of my Early Life (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1956), 179.

[2] C.S. Lewis, preface to George MacDonald: An Anthology: 365 Readings (New York: HarperOne, 2001 [1946]), xxxvii.

[3] Lewis, preface to George MacDonald: An Anthology, xxxviii.

[4] Lewis, Surprised by Joy, 179.

[5] C.S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (London: HarperCollins Children’s Books, 2011), 76-77.

[6] C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy, 213.

[7] C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy, 179.

[8] C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy, 181.

[9] C.S. Lewis, George MacDonald: An Anthology, xxxv-xxxvii.

[10] C.S. Lewis, George MacDonald: An Anthology, xxiii.

[11] Thomas Boston, Human Nature in Its Fourfold State: Of Primitive Integrity, Entire Depravation, Begun Recovery, and Consummate Happiness Or Misery in Several Practical Discourses (P. Mair, 1787), 324.

[12] Kerry Dearborn, Baptized Imagination: The Theology of George MacDonald (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), 11.

[13] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1924), 29.

[14] George MacDonald, Robert Falconer, from the 1869 first one-volume edition of Robert Falconer, Hurst & Blackett Publishers, London, 1869, ch. 10, p. 60.

[15] For a discussion of the schoolmaster and how it impacted young George, see Michael Phillips, George MacDonald: Scotland’s Beloved Storyteller (Minneapolis MN: Bethany House Publishers), 80-83.

[16] Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson, “Rooted Deep: Discovering the Literary Identity of Mythopoeic Fantasist George Macdonald.” Linguaculture 2014 (December 1, 2014), 29. Johnson recounts just how literary the MacDonald family was. “One of MacDonald’s maternal uncles was a famed Celtic scholar and editor of the Gaelic Highland Dictionary, who collected fairy tales and Celtic poetry in the midst of his campaign to keep the Gaelic language and culture alive; MacDonald’s paternal grandfather had supported the publication of an edition of Ossian—that controversial Celtic text that some claim kick-started European Romanticism and was certainly key to Goethe’s Young Werther; MacDonald’s step-uncle was a Shakespeare scholar; his paternal cousin another Celtic scholar; and his parents were both readers—his dad with an acknowledged penchant for Burns, Newton, Cowper, Chalmers, Coleridge, and Darwin, to name a few; and his mother with a classical education that included multiple languages.” Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson, 28.

[17] Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson, “Rooted in All Its Story, More Is Meant than Meets the Ear : A Study of the Relational and Revelational Nature of George MacDonald’s Mythopoeic Art.” Thesis, University of St Andrews, 2011, https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/1887, 53-55.

[18] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1924), 76.

[19] George MacDonald, in An Expression of Character: The Letters of George MacDonald, ed. Glenn Edward Sadler (Grand Rapids: MI: Eerdmans, 1994), 22.

[20] On MacDonald’s love of nature, see Michael Phillips, George MacDonald: Scotland’s Beloved Storyteller, 86-87.

[21] George MacDonald, Robert Falconer, from the 1869 first one-volume edition of Robert Falconer (London: Hurst & Blackett Publishers, 1869, ch. 41, p. 256.

[22] George MacDonald, David Elginbrod (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1863), 93.

[23] George MacDonald, cited in George MacDonald and His Wife, 108.

[24] George MacDonald, An Expression of Character: The Letters of George MacDonald, 17-18.

[25] Kerry Dearborn, Baptized Imagination, 18-19.

[26] Kerry Dearborn, Baptized Imagination, 27.

[27] George MacDonald, An Expression of Character: The Letters of George MacDonald, 24.

[28] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife, 154.

[29] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife, 178.

[30] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife, 156.

[31] At the time he accepted the pastorate, “he was working on ‘a poem for the good of my generation’, writing literary essays about poetry, avidly reading and translating the German Romantics, and building up a collection of literary books judged by one friend as not ‘likely to be of much service’ in ministry….Perhaps his congregation sensed his divided loyalties.” Daniel Gabelman, 'George MacDonald', in Literary Apologetics: The Imagination's Journey to God.

[32] MacDonald's scholarship has tended to view his teaching as something he took up out of economic necessity following his failed pulpit ministry. But Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson has shown that teaching literature was more than just a paid profession; rather, it was a vocation MacDonald took very seriously and corresponded with his own inclinations. Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson, “Rooted Deep: Discovering the Literary Identity of Mythopoeic Fantasist George Macdonald,” 34-35.

[33] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife, 318.

[34] Hein, Rolland. Christian Mythmakers: C.S. Lewis, Madeleine L’Engle, J.R.R. Tolkien, George Madonald, G.K. Chesterton, and Others (Chicago: Cornerstone Press, 2002), 5-6.

[35] C.S. Lewis, preface to George MacDonald: An Anthology, xxxii.

[36] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife, 324.

[37] Daniel Gabelman, 'George MacDonald', in Literary Apologetics: The Imagination's Journey to God, edited by Thomas Martin (De Gruyter Press, forthcoming).

[38] George MacDonald, An Expression of Character: The Letters of George MacDonald, 170.

[39] Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife, 547.

[40] Greville MacDonald, Reminiscences of a Specialist (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1932), 340-41.

[41] George MacDonald, Diary of an Old Soul, annotated and edited by Timothy Larsen (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2024 [1880]), reading for May 29, p. 128.

[42] The lacuna in the study of Victorian literature may be partly due to the fact that MacDonald’s novels, though they made perfect sense to 19th century readers, do not fit neatly into any of the contemporary boxes used for the academic study of literature. Daniel Gabelman summarizes the difficulty facing the modern reader coming to one of the novels for the first time. “The action of the novels is regularly interrupted by extended sermons on the one hand and by discussions of literature (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Dante, Shakespeare, etc.) and its interpretation on the other. Combined with the fact that many of MacDonald’s novels are already a strange hybrid of romantic descriptions of nature, gothic plotlines, and realistic depictions of human suffering, these long theological and literary reflections help make the novels into large, somewhat unwieldy chimeras—fantastic beasts of many mixed origins, which are consequently not as easily appreciated by unsympathetic readers.” Daniel Gabelman, 'George MacDonald', in Literary Apologetics: The Imagination's Journey to God.

[43] Marion Lochhead, The Renaissance of Wonder in Children’s Literature (Edinburgh, Canongate Publishing, 1977) 1.

[44] C.S. Lewis, preface to George MacDonald: An Anthology: 365 Readings, xxxiv.

[45] Here MacDonald aligns with the approach of scripture itself. In an earlier publication, I argue that the biblical authors place a rightly-ordered sense of beauty at the heart of the spiritual life. “Beauty and emotion are closely related in the moral life. Through the sense of beauty, we are moved out of indifference to become emotionally invested in pursuing one outcome rather than another. When Eve succumbed to the temptation to disobey God (Gen. 3:6), it was because the beauty of the tree and its effects ('pleasant to the eyes . . . desirable to make one wise') captured her imagination with greater force than the beauty of remaining faithful to the will of God. That example might lead us to disparage the role of beauty in moral decision making, and yet the same principle also works in the other direction as the Holy Spirit sanctifies our feelings, imagination, and aesthetic sensibilities. Through a sense of Christ’s beauty, we become emotionally invested in following Him. When we observe character traits in Bible characters and saints that are worthy of emulation, when we identify certain conditions as honorable or shameful, when our hearts are stirred in worship by 'the beauty of holiness' (Ps. 96:9), or when we order our actions based on a longing for outcomes that lie outside the scope of the present life but are attractive to the imagination—all these powerfully move us because they appeal, at some level, to our emotional dispositions. A rightly ordered sense of beauty is thus central to the moral imagination of the believer." Robin Phillips, Gratitude in Life's Trenches: How to Experience the Good Life Even When Everything is Going Wrong (Chesterton, IN, Ancient Faith Publishing, 2020), 110.

[46] George MacDonald, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture,” A Dish of Orts: Chiefly Papers on the Imagination, and on Shakspere [sic] (London, Sampson Low Marston & Company, 1983), enlarged edition 1895, 30-41.

[47] C.S. Lewis, preface to George MacDonald: An Anthology: 365 Readings, xxxii.

[48] “’Suppose my child ask [sic] me what the fairytale means, what am I to say?’ ‘If you do not know what it means, what is easier than to say so? If you do see a meaning in it, there it is for you to give him. A genuine work of art must mean many things; the truer its art, the more things it will mean. If my drawing, on the other hand, is so far from being a work of art that it needs THIS IS A HORSE written under it, what can it matter that neither you nor your child should know what it means? It is there not so much to convey a meaning as to wake a meaning. If it do not even wake an interest, throw it aside. A meaning may be there, but it is not for you. If, again, you do not know a horse when you see it, the name written under it will not serve you much. At all events, the business of the painter is not to teach zoology.’” George MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” Orts, 317.

[49] “A fairytale is not an allegory. There may be allegory in it, but it not an allegory. He must be an artist indeed who can, in any mode, produce a strict allegory that is not a weariness to the spirit.” George MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” 317.

[50] A fairtytale, a sonata, a gathering storm, a limitless night, seizes you and sweeps you away: do you begin at once to wrestle with it and ask whence its power over you, whither it is carrying you? The law of each is in the mind of its composer; that law makes one man feel this way, another man feel that way. To one the sonata is a world of odour and beauty, to another of soothing only and sweetness. To one, the cloudy rendezvous is a wild dance, with a terror at its heart; to another, a majestic march of heavenly hosts, with Truth in their centre pointing their course, but as yet restraining her voice. The greatest forces lie in the region of the uncomprehended.” George MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” 319.

[51] MacDonald did not want people to overthink his fairy tales, but to submit to their magic. “The best way with music, I imagine, is not to bring the forces of our intellect to bear upon it, but to be still and let it work on that part of us for whose sake it exists. We spoil countless precious things by intellectual greed. He who will be a man, and will not be a child, must--he cannot help himself--become a little man, that is, a dwarf. He will, however need no consolation, for he is sure to think himself a very large creature indeed. If any strain of my ‘broken music’ make a child's eyes flash, or his mother's grow for a moment dim, my labour will not have been in vain.” MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” 322.

[52] MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” 320.

[53] MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” 321.

[54] George MacDonald, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture,” 35.

[55] George MacDonald, “A Sketch of Individual Development,” Orts, 12-13.

[56] G.K. Chesterton, foreword to George MacDonald and His Wife, 11.

[57] C.S. Lewis, preface to George MacDonald: An Anthology: 365 Readings, xxxviii.

[58] George MacDonald, “A Sketch of Individual Development,” Orts, 49.

[59] C.S. Lewis, preface to George MacDonald: An Anthology: 365 Readings, xxxviii-xxxix.

[60] George MacDonald, “The Consuming Fire,” in Unspoken Sermons, First Series (London: Alexander Strahan, 1867), pp. 27-49.

[61] Brawley, Chris. “The Ideal and the Shadow: George MacDonald’s Phantastes.” North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies 25, no. 1 (January 1, 2006). https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol25/iss1/7.

[62] Crawford, Annie. “Meaning and Imagination: A 2024 Address for Graduates - The Symbolic World.” The Symbolic World, June 12, 2024. https://thesymbolicworld.com/content/meaning-and-imagination-a-2024-address-for-graduates.

[63] George MacDonald, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture,” 30.

[64] Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, translated by Constance Garnett (New York: Macmillan, 1922), 110.

[65] George MacDonald, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture,” 35.

[66] George MacDonald, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture,” 26-27.

[67] Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr. “The Nobel Prize in Literature 1970.” NobelPrize.org. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1970/solzhenitsyn/lecture/. Emphasis his.

[68] On MacDonald’s literary apologetics, see Daniel Gabelman, 'George MacDonald', in Literary Apologetics: The Imagination's Journey to God.

[69] George MacDonald, England’s Antiphon (MacMillan & Co Publishers, 1874), 4.

[70] John Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” The Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1918 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939), 730.

[71] George MacDonald, “The Imagination: Its Functions and Its Culture,” 25.

[72] George MacDonald, “A Book of Dreams,” in A Hidden Life and Other Poems (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1864) 99.

[73] George MacDonald, “Wordsworth's Poetry,” Orts, 246-47

[74] MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” 315.

[75] Goerge MacDonald, The Poetical Works of George MacDonald (London: Chatto & Windus, 1893), 259.

[76] MacDonald, “The Fantastic Imagination,” 316.

[77] Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1989), 18.

[78] George MacDonald, “A Sketch of Individual Development,” Orts, 60.

[79] For a review of the scholarship on MacDonald and Platonism see Dean Hardy, “The Religious and Philosophical Foundations and Apologetic Implications of George MacDonald’s Mysticism.” North Wind: A Journal of George MacDonald Studies 34, no. 1 (January 1, 2015). https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/northwind/vol34/iss1/7, 124-131. Hardy concludes that “MacDonald was a metaphysical realist who openly acknowledged that he operated under the shadow of Platonism.” Hardy, 131.